Norway’s Coastal Kitchen

Fresh ingredients, sourced where we sail

Cuisine that brings you closer

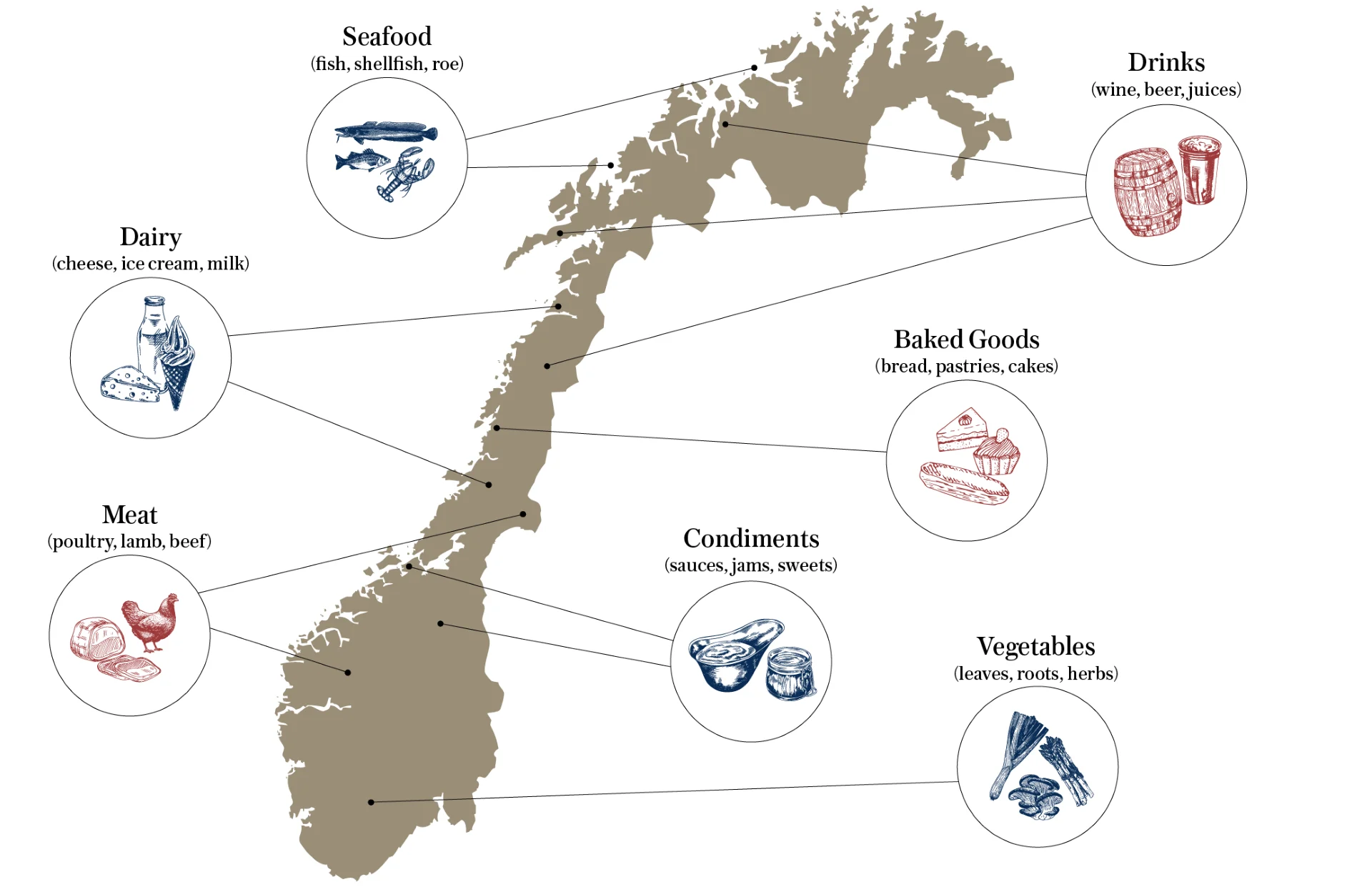

On a voyage with us you won’t just see the Norwegian coast; you’ll taste it too. As we sail its length, we pick from its pantry, sourcing the finest homegrown produce from the ports we visit.

We are proud to support 50 local farms, bakeries, and producers from across Norway. In our onboard restaurants, enjoy the likes of melt-in-your-mouth cod from Vesterålen, award-winning cheeses from Lofoten, and quality craft beer from Bergen.

Our onboard restaurants

In general, each of our ships has a main restaurant, a bistro-style eatery, and a fine-dining à la carte restaurant, all true to our food concept of authentic local cuisine.

Dining rooms typically have floor-to-ceiling windows so you can enjoy views of the fjords while you dine, connecting you to the very places where our ingredients are sourced.

Towards zero food waste

We place food waste from our fleet into a specially designed compost reactor in the port of Stamsund in the Lofoten islands.

Nearby Myklevik farm uses this fertiliser to grow new food for Norway and for our ships. It’s a simple, natural way to help local farmers and to keep our food waste as low as possible.

Head Chef Øistein Nilsen

Native son of northern Norway, Øistein spent much of his childhood exploring the great outdoors and appreciating the freshness and flavors of food from the wild.

As Head Chef for Norway’s Coastal Kitchen, he brings his vision of locally sourced cuisine to our iconic ships, while also championing homegrown talent, ingredients, and suppliers.

Culinary Ambassadors

We’re cooking up an exciting partnership with two award-winning Head Chefs from the Norwegian coast, Astrid Nässlander and Halvar Ellingsen, to enhance our menus and inspire the next generation of Norway’s Coastal Kitchen chefs.

Working closely with our own Head Chef Øistein Nilsen, they will do what they do best: craft locally inspired, sustainably produced, and delicious seasonal dishes, which will be unique to our voyages.

Taste the bubbles of the sea: Havets Bobler

Discover the story behind this sea-aged, sparkling sensation, created exclusively to serve on our ships.

Sustainable and seasonal

Sourcing our food locally isn’t just about fresh, farm-and-fjord-to-table flavors. It’s also about achieving the lowest footprint possible and making sure there is minimal food waste.

By carefully managing supply and seasonality, we believe cuisine can and should be kind to the planet while still tasting authentic and amazing.

Choose how you want to discover our home, the Norwegian coast

- Multiple offers

Roundtrip Voyage from Bergen | Explore Norway’s Coastline

Route

Bergen - Kirkenes - Bergen (Roundtrip)

Departure Dates

Regular departures - 12 days

Price from $3,434

$2,404

Ships

Multiple

- Multiple offers

11-Day Norwegian Voyage | Bergen - Kirkenes - Trondheim

Route

Bergen - Kirkenes - Trondheim (Roundtrip)

Departure Dates

Regular departures - 11 days

Price from

$3,434

Ships

Multiple

- Multiple offers

7-Day Norwegian Voyage: Northbound | Bergen to Kirkenes

Route

Bergen - Kirkenes (Northbound)

Departure Dates

Regular departures - 7 days

Price from $2,336

$1,635

Ships

Multiple